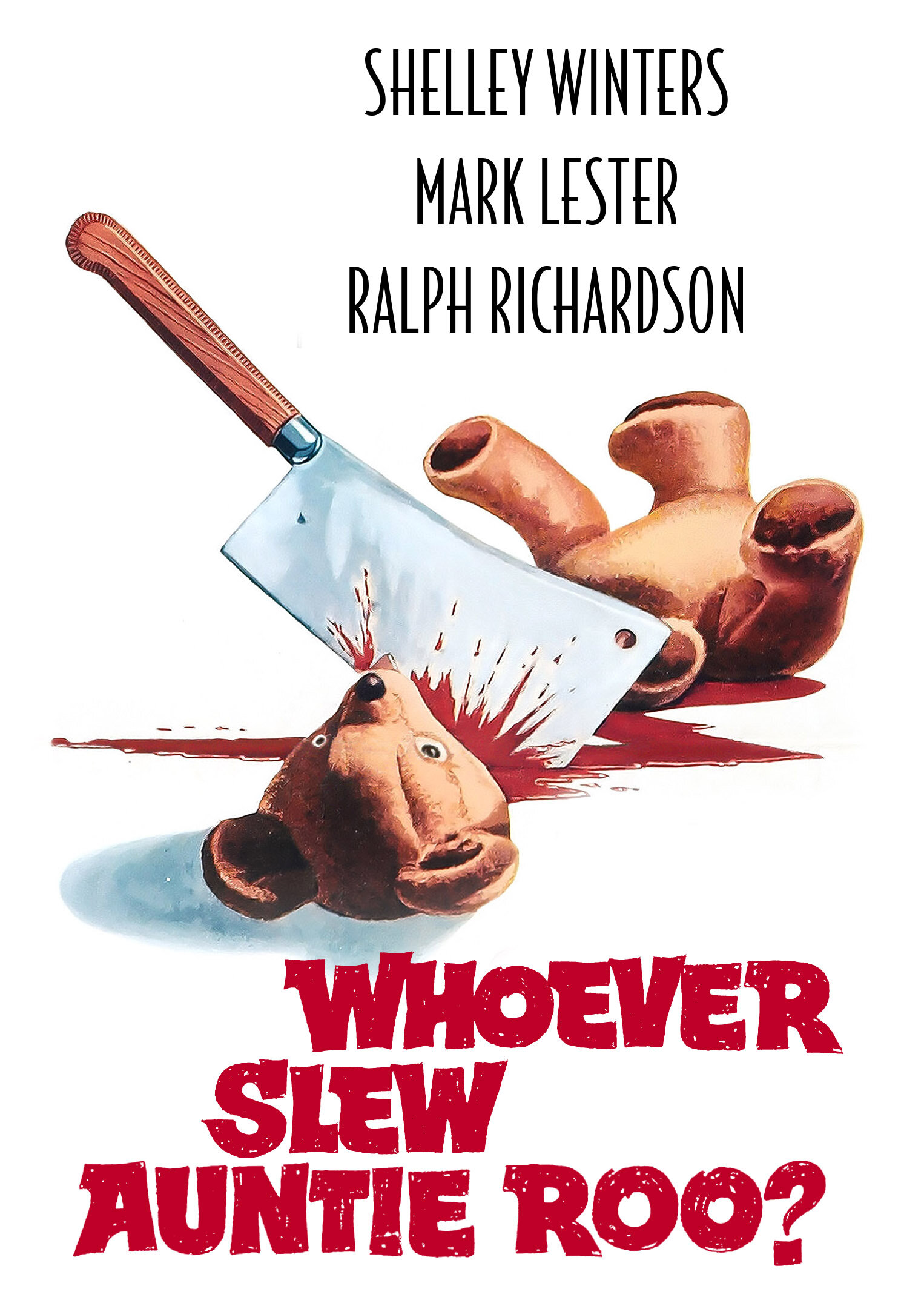

Whoever Slew Auntie Roo?

Let’s talk about witches.

Witches are a staple of folk lore all over the world, like magical animals and child endangerment. When talking about fairy tale adaptations, we’re going to run into a lot of witches, but here’s where my problem starts. I don’t know about you, but when I think about Western style witches I can’t help but think of all the real people executed for witchcraft throughout European and American history. All that actual tragedy can really get in the way of my fun horror movie watching. The fairytale witch is inseparable from the misogyny that created her. While there were men who were accused and executed for witchcraft, the fact that I’ve met people don’t know ‘witch’ is actually a gender neutral word is demonstrative of how much the witch's monstrosity is tied to her femininity. The history of witchcraft is the history of an idea, an idea that morphs between devil worshiping heretic, misunderstood pagan, halloween decoration, and reclaimed feminist icon.

All of this preamble is to give you, dear reader, a peek into my mindset as we look at three very different films tackling one of the most famous witches in fairytales - the candy obsessed, child eating hag from Hansel & Gretel.

I have nothing quippy to say here, I think this is a dope poster. Classic.

Whoever Slew Auntie Roo? Is a 1972 horror film directed by Curtis Harrington and stars Shelley Winters as Mrs. Ruth Forrest. Mrs. Forrest is a retired performer living alone in her large English estate - a house the children in the nearby orphanage call the Gingerbread House. See, Auntie Roo, as she likes to be called, is quite generous and invites children from the orphanage over for a big Christmas feast. That’s right - this is a Christmas horror film!

It’s hard not to feel bad for Auntie Roo early on. Her staff is stealing from her and worse they’re in cahoots with a drunken charlatan who puts on phoney seances to contact the spirit of her daughter Katharine who died in a tragic bannister sliding accident. So sure, she’s a little desperate, and kooky, and sings to the mummified corpse of her daughter at night, but she’s not hurting anyone. Oh, did I not mention the corpse daughter? The first scene of this film shows Ruth singing to a girl in a crib, only for the camera to rotate and show us the grizzly body right out of an EC Horror comic and then THUNDERCLAP! The movie wants that image in your brain, lest you be too sympathetic to Ruth as the story continues.

dun dun DUN!!!!!

Two of the local orphans, Christopher and Katy, are initially not invited because they were apparently too sulky about being recently abandoned , but these two scamps sneak into the party anyway. When they get there, Ruth is quick to form an attachment to younger sister Katy and does some heavy-duty projection onto the girl once she picks up Katharine’s old teddy bear. Before Christmas ends she wants to adopt the girl - her older brother….eh not so much. Christopher has a lot of sway over his younger sister and tries to keep her away from sweet Auntie Roo, partially because he sneaks into the nursery through the dumb waiter to see the corpse daughter, but Auntie Roo takes matters into her own hands and quietly kidnaps Katy. Not that Katy seems to mind, as she’s fed sweets and given gifts. Christopher goes back in to rescue Katy but is snatched himself. Throughout the film, Christopher refers to the actual fairytale of Hansel and Gretel, narrating it to himself. He becomes convinced that Auntie Roo is going to cook and eat them. But … does he actually believe that?

While Auntie Roo is clearly unhinged, it is obvious that she’s not trying to kill and eat anyone. It is established early on that Christopher is a habitual liar and tells scary stories to the younger kids; when Katy tells him that Auntie Roo has a secret stash of expensive jewelry, Christopher reminds her that it’s okay to lie to others but never to each other. Christopher is excited about those jewels, though, and remembers to grab them while trapped in the Forrest House, stuffing them into the toy bear (curiously this is the second film Shelley Winters has been in where two children hide a treasure in a stuffed animal while being menaced by a fairytale monster), and he is not letting that bear out of his sight - he even runs back into a burning building to get it. This is after they burn Auntie Roo alive, you see.

Through a series of clever misdirections, Christopher and Katy are able to trap Auntie Roo in the pantry. While she tries to Jack Torrence her way out of the pantry with a butcher knife, they stack firewood in front of the door and set it ablaze. The fire department arrives but it’s too late, and the two kids lie their little butts off, talking about how sad it is while they smile to each other like the little sociopaths they are. It’s a surprisingly mean spirited adaptation about how two kids rob a mentally ill woman and then burn her alive without any consequences.

This film is sometimes referred to as a hagsploitation film. That tasteful name refers to a subgenre of horror movies that sprung up after the popularity of Whatever Happened to Baby Jane? These films tend to have amazing actresses who were certified Movie Stars. Hollywood didn’t know how to write starring roles for women over fifty though, but B horror movie directors had their arms wide open looking to add some class to their schlock. And this is the pleasure of these films - to see Oscar winning Shelley Winters menacingly eat an apple, sing to a mummy, and be totally unhinged. But what really makes Auntie Roo monstrous?

Burn the witch.

When she’s about to be burned alive, she isn’t screaming about the fire but that she doesn’t want to be alone. The song she sings to her daughter in the beginning, and throughout of the film, is the folk song Sprig of Thyme, which warns young women not to be too free with their love because men only want them when they’re hot stuff and then will leave you when you’re old (I’m pretty sure I’m reading that right, the whole thing is heavy with plant metaphors). You see the real problem with Auntie Roo is that she’s past her prime, and driven crazy by the fact that she doesn’t have children. In a way, this film mirrors the reasons some real women were accused of being witches - age, independence, covetous neighbors, and mental illness.